From Inflated Expectations to Informed Practice: AI’s Next Chapter in Education

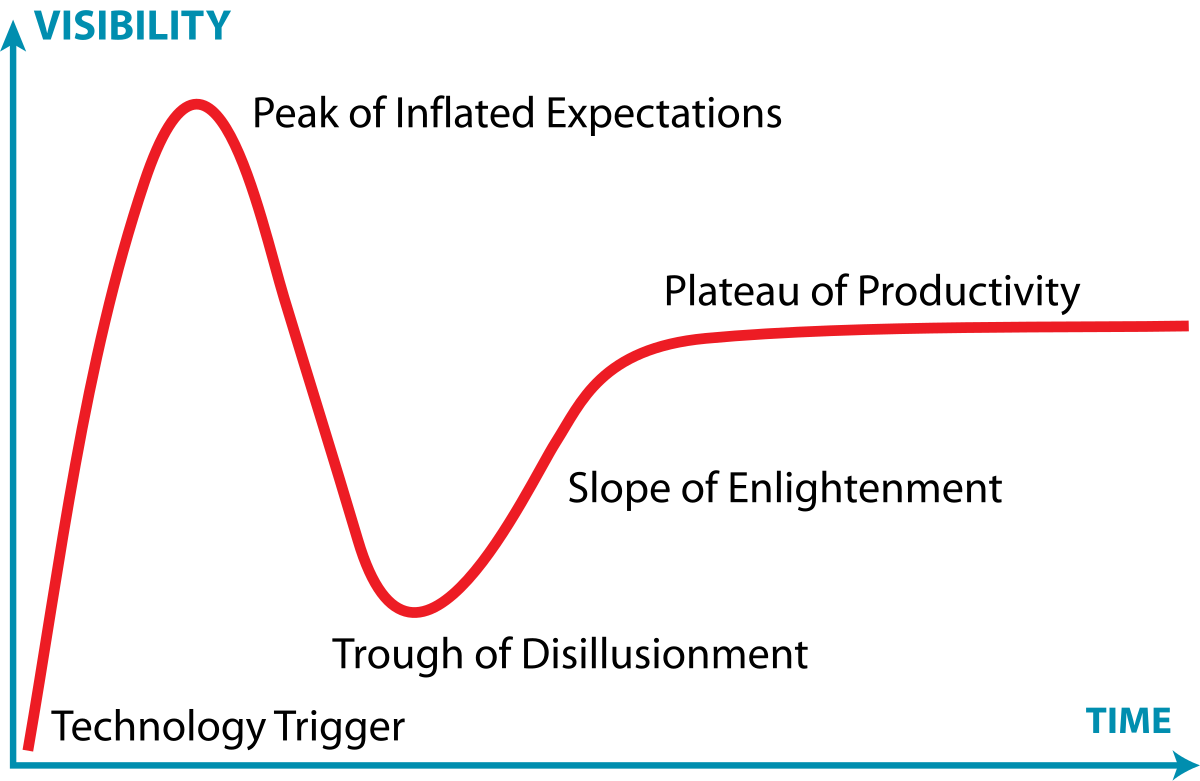

I was recently asked at a family gathering over the holidays about the true potential of AI in education and whether or not its been overhyped. I’ve read a LOT about this exact topic, and I’m starting to develop a clearer idea of where this is all heading. Here’s my perspective at the start of 2026: it is finally getting easier to say the quiet part out loud about AI in schools. The technology is real, the potential is real, and the marketing has been wildly optimistic, but if you want a framework that explains why so many educators feel both energized and underwhelmed at the same time, the Gartner Hype Cycle is a helpful lens. Not because it predicts the future with precision, but because it describes a pattern we have lived through repeatedly with education technology. A new technology appears, expectations soar, reality intrudes, and then, if we are patient and thoughtful, the technology settles into something genuinely useful.

The hype cycle was developed in 1995 by Jackie Fenn - an analyist at Gartner, Inc. (a reserch and advisory firm) as a way to explain the predictable pattern of excitement, disappointment, and eventual productivity that follows the introduction of new technologies. It was designed to help organizations make more informed decisions by separating early marketing driven enthusiasm from realistic timelines for adoption and impact. Over time, it has become a widely used framework for understanding why promising technologies often feel overhyped before they become genuinely useful. If you think about any technology used in education - the exact same cycle can be used to describe it.

The early days of generative AI followed this script perfectly. Large language models like ChatGPT reached students before the teachers even knew about it. I clearly remember the first time I entered a prompt - the results were breathtaking. Headlines promised instant learning personalization, effortless differentiation, and the end of our typical methods of assessment as we know it. For a brief moment, it felt like education had found a shortcut around the hardest problems we face. Then classrooms and teachers did what classrooms always do. They complicated the story. Teachers discovered that a tool that can generate text is not the same thing as a tool that builds understanding. Administrators discovered that adoption without training creates confusion, not innovation. The slide from inflated expectations toward disillusionment began, not because AI failed, but because learning resisted automation - as it almost always does.

Recent reporting reflects this shift in tone. Articles that once focused on novelty now emphasize friction. Schools experimenting with AI are finding that the real work is not turning tools on, but deciding when not to use them. Journalists have highlighted that national efforts and district pilots alike are increasingly cautious, prioritizing teacher preparation, age appropriate use, the impact of AI on the humanities and creativity, and evidence of impact over speed. The promise of a universally transformative rollout has given way to a slower and more realistic conversation about where AI helps, where it distracts, and where it simply does not belong yet. And in my opinion, that is a very good thing. I much prefer a cautious and thoughtful approach to the integration of any technology in schools, rather than quickly adopting it just to do so.

This is an example of the trough of disillusionment on the Gartner curve - and why that phase of the curve is so important. It is the phase where we stop asking whether a technology is impressive and start asking whether it is instructional. It is also the phase where systems realize that governance, privacy, assessment design, and professional development matter more than vendor demos. Importantly, this is not a dead end. Historically, this is the phase that separates tools that fade away from tools that quietly become indispensable.

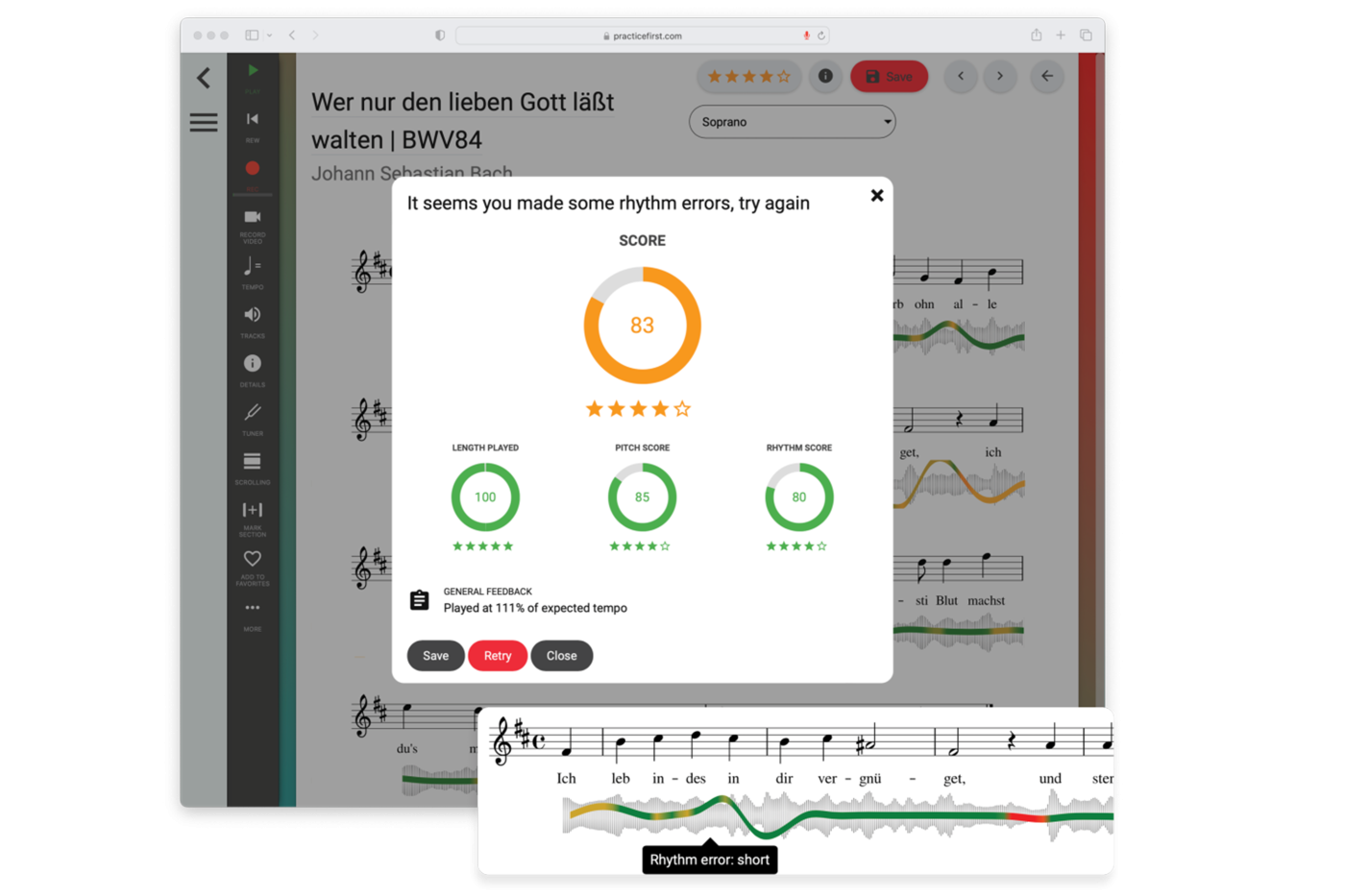

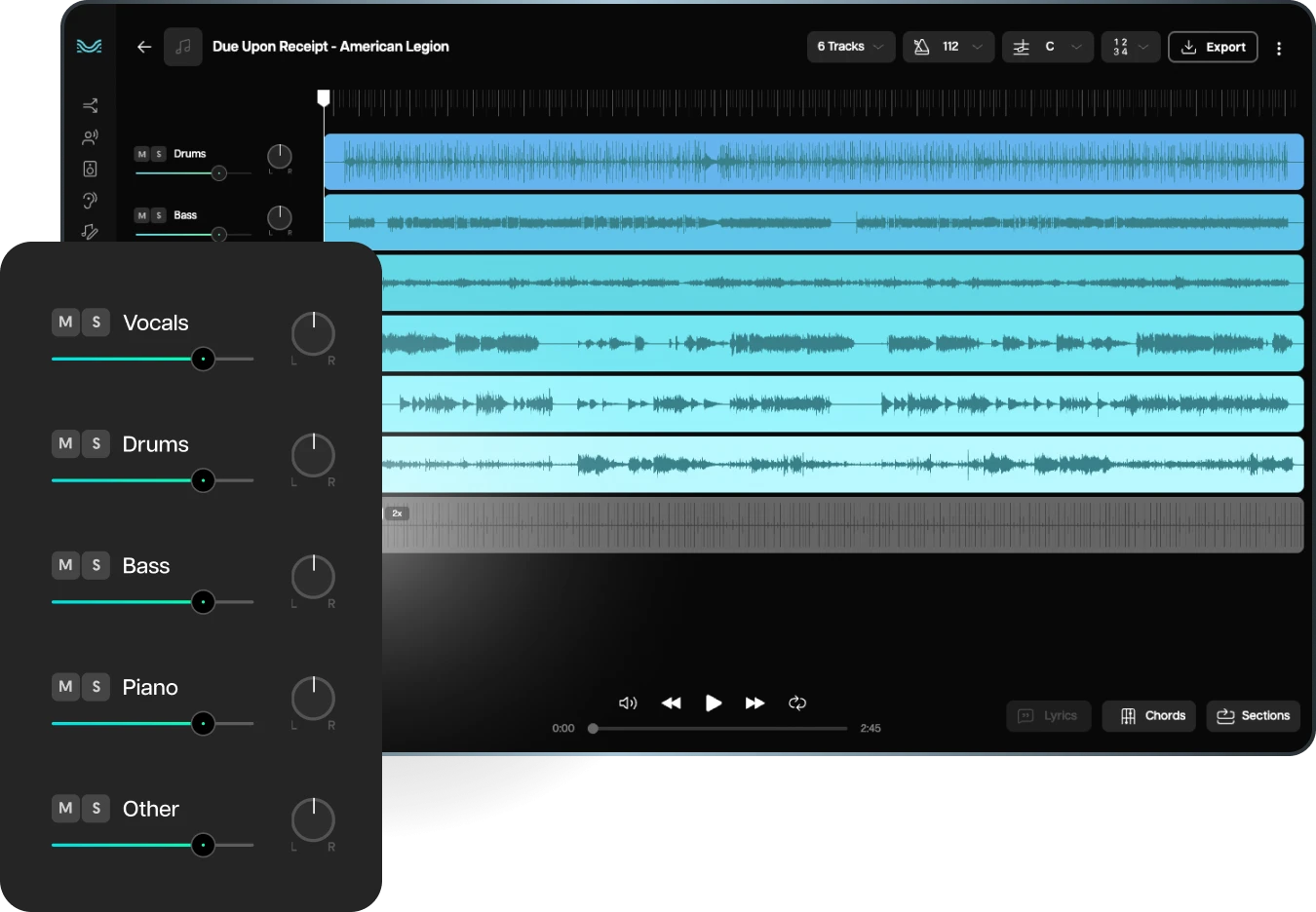

I think that music educators feel this shift in particularly distinct ways - and there are some distinct bright spots as well as points of concern when utilizing AI-powered tools in the music classroom. Unlike text based subjects, music learning is deeply process driven. The hype around AI composition tools like Suno and Udio (and the IP issues surrounding them) have ultimately made many teachers simply avoid using them as a music making tool in their classrooms. That said, tools are actively being used - take things like PracticeFirst powered by MatchMySound, Moises and others afford students accurate and richly descriptive automated feedback and amazing functionality like track separation that can be used as practice tools across all aspects of a music program. In practice, many music teachers are discovering that AI’s value is not in replacing musicianship, but in supporting it at the margins. Tools that help students practice more effectively, visualize mistakes, explore harmonic possibilities, or reflect on performances can extend learning beyond the rehearsal room without undermining the human core of music making. At the same time, music teachers are often the first to notice when AI shortcuts threaten students’ creativity or encourage students to bypass listening, revision, and learning. For them, the hype curve is less about fear of replacement and more about protecting musical thinking in an age of easy answers.

Climbing the slope of enlightenment means making deliberate choices. It means using AI to reduce low value administrative work while preserving high value cognitive work. It means designing assignments that reward process, reflection, and evidence, rather than polished outputs alone. It means teaching students how to use AI as a support, not a substitute, and being explicit about when its use is appropriate. For music educators, it means choosing tools that deepen listening, refine technique, and encourage creative decision making, rather than tools that simply generate sound. I don’t know many music educators who love doing admin work and that is where AI tools can shine.

The plateau of productivity, if we reach it, will not be dramatic. It rarely is. It will look like fewer headlines and more quiet competence. AI will become something teachers use without fanfare, because it reliably solves specific problems without creating new ones. Gartner’s Cycle reminds us that disappointment is not failure. It is a necessary step between marketing and meaning. I firmly believe that in 2026, the conversation around AI in schools is finally maturing. Less breathless enthusiasm. Less panic. More pedagogy. More evidence. That is how educational technology grows up. And that is how AI, including in music classrooms, moves from a moment of hype to a place of lasting value.